Design Systems at Gusto

At Gusto we’ve been building our design system for the past two years and thinking about how to scale our product and design process across multiple complex projects and teams. So whether you’re just starting out building a complicated front-end, or if you’re getting ready to build a style guide at a large organization then hopefully you can learn from some of my mistakes that I’ve jotted down below.

Because oh boy I made a lot of them.

Why does Gusto even need a design system though? Well, when I joined the payroll team in June 2016 we identified some issues with the design and development process. There was no pattern library or style guide and the team had nine product designers with a large number of engineers and project managers distributed into missions. The problem with all this is how the communication between those missions had begun to silo into even smaller groups and ultimately this led to a large, confusing front-end codebase.

Your coworkers might not be able to identify a problem and call it an issue with the overall design system, but everyone feels the pain. Product designers will struggle to figure out which components or templates to use, PMs will find that projects take much longer than they first expected and engineers will become frustrated since they spend a lot of time building custom UI. Of course, this is always going to be the case when a company grows to a certain size.

All of these issues stem from a lack of communication though, regardless of how outstanding or smart or brilliant the team might be. If great designers or engineers don’t communicate with one another then these issues are simply inevitable. So it was at this point that I rolled up my sleeves, opened up my code editor, and prepared to fix everyone’s problems by myself.

This is when I learnt the most important systems design lesson.

Lesson #1: You can’t build a design system by yourself

I genuinely believed that I could hide in the darkest corner of the office, design a great system, build an outstanding front-end, and return to the team a hero. But! There are no heroes in this line of work. In fact there’s a great episode of the podcast Track Changes where Paul Ford and Rich Ziade talk about the social dynamics of legacy code. Paul mentions that:

The worst thing you can do for your organization is prove how smart you are.

Oof. When I heard that I realized that I had spent an awful amount of time trying to be the smartest and most brilliant guy in the room and this ultimately led to some friction within the team. No one wants to work with the guy that’s dictatorial and mean. He’s just a jerk.

It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the most successful projects were the ones where I introduced other designers and developers into the process early on. From refactoring our icon system, to a typography refresh, to removing Bootstrap styles from the app, everyone had great feedback beforehand where we could lean on their experience to improve the system.

Also, the important thing to remember about design systems work is that although everyone wants the same outcome, it’s how to go about it that’s the tricky part. And since every org and engineering culture is different I found that the advice from other teams I had read about wasn’t all that helpful to me. But one issue that every development and design team out there has in common is the need for a single source of truth—a home to represent all of their code and design. That way everyone can contribute in a scalable manner without hiding in their own teams and building custom UI all the time.

Anyway, after several days and nights hacking things together, my pal and boss Dora Chan returned with a prototype of what would soon become The Guide.

And it was wondrous.

As we started to flesh out Dora’s prototype we had three goals that drove all of our decisions:

- Set high standards for design and front-end development.

- Document how components can be used for all teams.

- Reign in the code and design inconsistencies we found in the app.

This is something that all teams of a certain size need and so it’s unlikely that this news to anyone at this point. However, I think it’s easy for these sorts of rules to become mean and nasty given the right tone. So in the introduction to The Guide I set out to inform the team of our goals in a more collaborative spirit:

This is where all of the documentation for Gusto’s design system is archived for safe keeping; it contains all the assets you need, such as images and illustrations as well as notes on our copywriting style and documentation for our React components. In fact, we like to think of The Guide as a sort of Pokédex.

Ideally this is where we can share information and collaborate in a public space to gain consensus across missions in terms of code, design, accessibility, performance, and branding. If we improve a single component here in The Guide then all of our apps and features will reap the rewards at the same time in a predictable manner.

Building The Guide was tough going though. It required taking all of our code out of our main app, cleaning it up, and placing it into a new repo called the Component Library. This way we would have a common group of components that could be used in any application that Gusto builds for the future. But a great deal of time was spent talking to engineers and designers about this plan and imagining a future where design and development was not only easy but breezy, too.

Lesson #2: A design system doesn’t have to be complete to be useful.

Having all our components in a separate repo ultimately meant that we could use it as the foundation for design at Gusto: every time we wanted to create a new app we could depend upon these settings and styles being consistent and easy-to-use without have to build the whole dang thing from scratch. But we were worried about it being incomplete and unfinished; there wasn’t good documentation for all our styles or even a list of which propTypes were available in our React components, for example.

However as soon as we released The Guide we found that the engineering and design teams at Gusto started using it, even though it was unfinished. This was shocking because The Guide was always our north star for how we wanted to build products and features but it was never as great as we wanted it to be, at least in the beginning. We very slowly pushed improvements to it over time and we were far too hesitant to change anything until it was perfect. Yet after watching the teams at Gusto jump on it so eagerly I now believe that all style guides should aim to be useful but being messy is okay, too.

Great visual design or even the UX of a style guide isn’t anywhere near as important as the documentation being in a single location that everyone can easily find. And if our work saved an engineer or designer five minutes asking someone else on Slack about how to use component X then The Guide is a success, if only a small one.

Lesson #3: Design systems live and die by their documentation.

It was around this time that I learnt my third lesson of systems design work: it’s not just about refactoring older components and coding. Style guides require enormous amounts of careful, deliberate writing and I shortly found that the copywriting is just as important as the code.

And considering we were only two designers doing this work (mostly as a side project) we knew we couldn’t sit down and explain The Guide to everyone that joined the company. So another goal of ours was to ensure that designers and engineers could explore what the system was capable of without having to ask questions all the time. The Guide should ultimately feel like a playground where you can quickly take LEGO blocks and build whatever you want from it. But that took a while to figure out, too. After months of work I found that a style guide is less helpful when it orders people to do something.

Exploration in a design system needed to not only be possible then, but actively encouraged—I imagined that The Guide had to be a warm and welcoming place for any developer or a designer regardless of experience. In short; kindness was the key.

Lesson #4: A design system is more than code and design — it’s a record of shared knowledge.

I think most systems designer folks work this out early on in their careers but it took an extraordinarily long time for the shoe to drop for me. And that only started to happen when I read the ever-so-excellent Design Systems by Alla Kholmatova where she writes:

Sometimes we think other teams have got it right and aspire to build a system just like Airbnb. But every approach has its downsides. […] At the heart of every effective design system aren’t the tools, but the shared design knowledge about what makes good design and UX for your particular team and your particular product. If that knowledge is clear, everything else will follow.

With this little book I learnt that if a design system doesn’t solve the needs of designers and engineers then they’ll feel that the system is getting in the way of their work. My pal Jules Forrest described it like this:

Design teams aren’t explicitly rewarded for reusing designs the way engineers know they should write DRY code, so introducing inconsistencies feels like productivity.

So how do we build a design system where the opposite is true? How do we make adding inconsistencies to a design system feel unproductive? Well, I think it’s important to note that designers and engineers introduce inconsistencies to a system not because of the code quality necessarily but due to a flurry of other reasons: poor documentation in a style guide, the naming structure of our components, the inability to quickly scan for what they need.

This means that design systems are more about evangelism than almost anything else. And what I originally assumed was a coding and programming gig turned out to be nothing of the sort — this line of work ended up being about 10% code and 90% collaboration, research, and mentorship.

This is when I realized that style guides aren’t important because they accurately represent the codebase, and they’re certainly not important because they create rules and regulations across a network of teams. Instead, style guides are important because they’re a gathering space. They decrease the social complexity of an organization because all that knowledge can be stored and leveraged.

The Future of Design Systems

I always find it funny when people talk about the future of X or Y, but if I were to take a wild guess about where all this is leading then I wouldn’t bet on the tools—they’re not really the most important part of design systems work. Style guides are helpful for sure, although it’s a little more complicated than that.

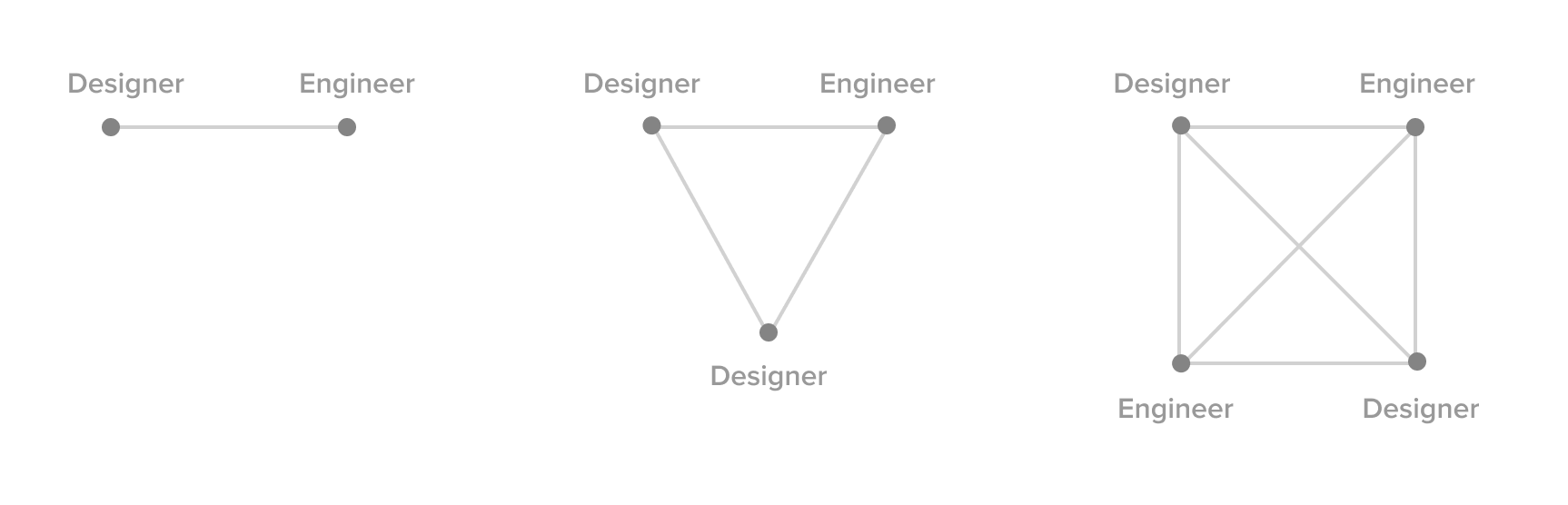

Bear with me for a second, but a short while ago there was a great post by Austin Kleon about how the relationship with his family changed with the birth of his second son. He made a graph that pinpoints the relationships between him, his wife, and his children, representing each of them as nodes in a complex network that gets exponentially more complicated with every addition to the family. Austin doesn’t have to just deal with his relationship with his son, but he now has to be concerned about the relationships between his sons, too.

And the same is true of a design team. With each new addition the relationships between all of the designers increases in complexity, and only gets more complicated when you think about their relationships with product leads, engineers and project managers.

Style guides and pattern libraries are important to tackle the inevitable miscommunication errors that pop up in between these complex relationships. However! The real goal of design systems work is to make sure that these relationships are fruitful and in sync with one another from the get go: all of our efforts should be focused on decreasing the social complexity of our teams. That’s the future of design systems.

At least, it’s how I’m thinking about all of this today.